|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

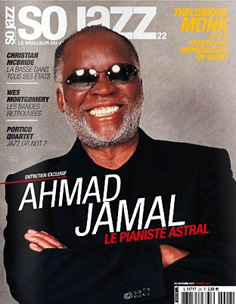

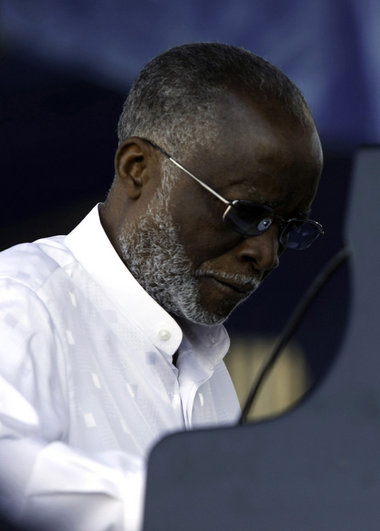

Ahmad Jamal unleashed 80 years of keyboard smarts at New Orleans Jazz Festival... |

|||

|

||||

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

The new MUSIC ... |

||||

|

||||

|

The new DVD ... |

||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

After Fajr |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

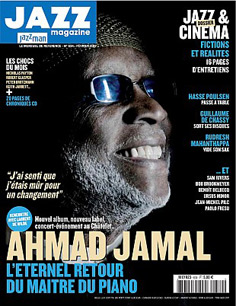

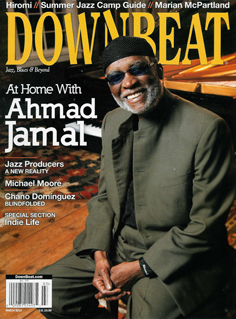

| Sounds of the 70s Two great new jazz albums from aging pianists. By Fred Kaplan Posted Friday, May 30, 2003, at 10:52 AM PT Two of the year's most invigorating jazz albums—Ahmad Jamal's In Search of Momentum and Martial Solal's NY-1—are by pianists in their 70s whose careers are in breezy renewal. Jazz has its share of septuagenarians playing nearly as spectacularly as they ever have—Sonny Rollins, Lee Konitz, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman. But I can't think of anyone who, in the process, has so re-energized, even transformed his sound as Ahmad Jamal. Jamal achieved huge fame in the mid-'50s for his elegant treatment of standards and for his finger-snapping original, "Poinciana" (which rose to the top of the pop charts). Miles Davis proclaimed Jamal a major influence: He emulated Jamal's soft touch and spacious phrasing; he told his pianist at the time, Red Garland, to play like Jamal; his albums of the era feature many of the same ballads Jamal played ("Just Squeeze Me," "My Funny Valentine," "But Not for Me"). Miles moved on—inspired, in part, by new piano stylists, the bluesy Wynton Kelly and the harmonically inventive Bill Evans—but Jamal didn't. Jamal always possessed a stately swing, but it could easily devolve into stuffiness. I once saw him on a talk show in the '80s, ponderously protesting the word "jazz" as a nasty vulgarism, insisting that it be called "American classical music." Both he and his music lacked a certain spontaneity and joy. That charge can no longer be leveled. In Search of Momentum bristles with wit, drama, even adventure. It cooks, it simmers—when it needs to, it boils—all without sacrificing a wisp of grace. Something happened to Jamal this past decade. The neon signs first flashed on his 1994 album, The Essence, Part 1. Suddenly, his left hand, once content to weave lush chords, was pounding out dense, discordant clusters; his right hand, while never untethered from the structure of melody, flitted and prowled on a looser, janglier leash. The album didn't quite hold together; he was exploring new concepts without yet adopting any (his new disc's title, In Search of Momentum, would have been more suitable for that one), but it offered an intriguing glimpse of possible coming attractions. His new CD provides the full picture. Jamal has completely integrated the lithe lyricism of old with the muscular passion of new. It's clear from the opener, the title tune: a clarion anthem in the middle registers, clanging chords way down low. The second song, "Should I," is a jaunty number but with an edge. Jamal displays extraordinary dynamic range and fine precision at each shade, moving from crystalline triplets to heavy block-chords and back again without a seam. His rhythm section, which has been with him since The Essence, provides more color and counterpoint than mere accompaniment. James Cammack plucks the bass strings hard; the thing growls while it walks. Idris Muhammad crackles all around the rhythm on his trap set, smacking the snare in unexpected places, suggesting the beat rather than pedantically counting it. When Jamal moves from hard to soft, it's as if he's shifting first in synch, then in contrast, with his players, which lends a piquancy to the song title. Songs, including song titles, have—always have had—meaning for Jamal. On "I've Never Been in Love Before," he rushes through a recitation of the melody but backs it with evenly paced, rhythmically deft chord changes, making the line sway in spite of itself. Deeper into the song, he shifts from single-note melodic phrases to heavily embroidered bursts, or he rushes ahead of the beat, then lags behind, creating a cauldron of tension, the sense of anxious longing yet also tenderness that lies at the heart of this standard. On "Where Are You Now," he insouciantly dashes across the keyboard like a sonic Astaire, effortlessly fluid; the trills aren't abstract or gratuitous, they convey the fleeting feel of seeking. The only weak spots of the album are "Whispering," which features an over-the-top velveteen singer, and the final two tunes, Monty Alexander's "You Can See" and the standard "I'll Always Be With You," both edgelessly bouncy. Otherwise, the disc is a thrill: spry, dashing, tight but loose—Jamal's majesty without the dread hush. Maybe he'd even dare call it jazz. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Nature

Atlantic 3984-23105-2 |

|||

The new book ...

The Ahmad Jamal Collection

Artist Transcriptions - Piano

|

|

Ahmad Jamal: Always Making Jazz Seem New

|

|

|

Los Angeles Times

FRIDAY May 11, 2001 |

|

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY APRIL 18, 1999

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Loved the LP, Waiting for the CD

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Not so jazz LP's. While it's easy to find landmarks, the "kind of Blues" and "Giant Steps," many outstanding albums by important artists have yet to be reissued on CD. Some are lost in the limbo of legal disputes; others have simply been overlooked, often because changing tastes have rendered them temporarily unfashionable. Here, for example, are 13 first-rate jazz albums recorded from 1955 to 1982, none of which has ever appeared on CD in the United States. AHMAD JAMAL: 'CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE NEW JAZZ' ARGO, 1955 Through Mr. Jamal's "classic" trio, with Israel Crosby on bass and Vernel Fournier on drums, is amply reresented on CD, this influential record by the pianist's earlier, ddrummerless group, with the guitarist Ray Crawford in place of Mr. Fournier, remains unavailable. The Jamal fan Miles Davis must have worn our at least one vinyl copy - "All of You," "It Ain't Necessarily So" and Mr. Jamal's own "New Rhumba" all turn up on Davis' Subsequent albums. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

||

| Ahmad Jamal Trio

Through Sunday Highly recommended Forty years after commanding attention as one of Chicago's leading ongoing attractions, pianist Ahmad Jamal continues to hold this city's jazz fans in the palms of his busy hands. That he is able to maintain their devotion, having evolved into a very different stylist, tells you two things: Unlike some veteran artists, he has never lost the ability to renew himself, Nor has he lost his gift for pleasing average listeners without compromising his art one bit. Jamal has always been a master of dynamics. They are his bread and butter. He thrives on abrupt shifts in time and tempo, contrasts between light and dark and shrewdly designed games of tension and release. He attacks his panoramic canvases like an action painter, continually splashing the surface with bold effects without ever relaxing his involvement in the nuances that give them character. Standard song form can't contain him. Even in his most laid-back moments, his notes run over the sides. But for all that, Jamal has never revealed the bite and propulsive power he did Tuesday at the Jazz Showcase, where in recent times only McCoy Tyner has created as much keyboard excitement. |

|

|

| Concerning himself less than usual with flashing instructions to his bandmates, he did conducting through his emphatic playing. Much of the set was poised between convulsively hammered bass notes and delicate, sweetly turned figures higher up on the keyboard. There were fractious phrases and atonal touches to start the set and flights of lyrical fancy to finish it.

Much of the excitement could be credited to the outstanding chemistry of the trio. It included Chicago bassist James Cammack, a longterm, on-and-off associate of Jamal's, and veteran drummer Idris Muhammad, the latest in a series of accomplished New Orleans battery men to back him--and possibly the most hard-edged. It can't be easy keeping up with Jamal's mood swings, particularly on the first night of an engagement. |

But Cammack and Muhammad were with him on every hairpin transition, grinning in surprise, whether bringing a dark, primal urgency to "Wild is the Wind" or dancing on themelodic curves of a freewheeling treatment of "Easy to Love."

Muhammad, who has showed off the Crescent City funk side of his talent at the Showcase backing guitarist John Scofield, reveled on this occasion in hard knocks--in thudding rim shots and resounding malleted cymbals and steady drilling on his snares. But when you're discussing a Jamal trio, there is no taking anyone's contribution out of context. Through example and inspiration, this pianist exerts his will every step--and side-step--of the way. Lloyd Sachs |

|